Nepal’s National Health Insurance Program (NHIP) urgently needs life support. Last spring, amid the staccato of machines saving my father’s life, I listened to the pain of other patients and their families.

Before transferring my father to a higher centre in Kathmandu, I heard murmurs among a long line at the local hospital’s insurance billing counter. Families spoke of delays in admissions and discharges. Many critically ill patients had maxed out their health insurance coverage on the first day.

Public trust in the NHIP and the Health Insurance Board is waning. Hospitals are not being reimbursed, and care is not smooth for most patients. This is not a crisis of access; it is a crisis of policy implementation.

Started in 2016, the NHIP was intended to help Nepalis cope with high health expenditures. Estimates from Colombia suggest that a country needs to spend up to 20 percent of its GDP to achieve this. Nepal spends less than five percent.

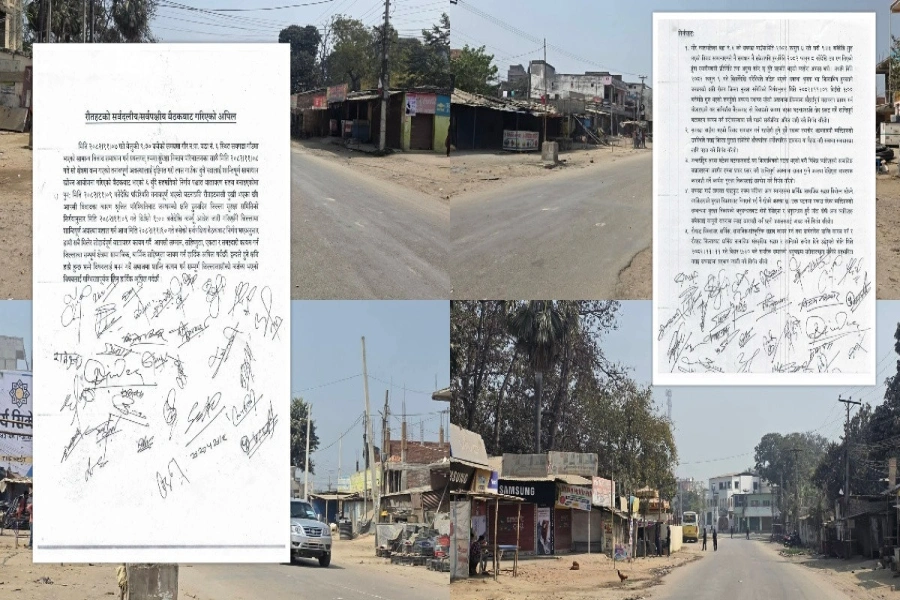

Insurance authority issues directives on monetary loss insuranc...

Reports show that the NHIP is suffering from low renewal rates and adverse selection—patients opt for subsidised universal coverage only when they need treatment. About 10 percent of patients face catastrophic illnesses such as cancer, stroke and heart attacks, leading to high out-of-pocket (OOP) spending and financial hardship. Currently, more than 50 percent of the population pays OOP expenses. For a country with a nominal GDP of around $2,000 per capita, the implications of such health shocks can be devastating for families.

The current model has an annual premium of NPR 3,500 for a family of five. This figure is neither based on the median nor the mean. There are no bronze, silver, gold or platinum tiers, as seen in Western systems. The current ceiling of NPR 100,000 per family essentially reflects a “you get what you pay for” structure when the contribution is only NPR 3,500. For families that can afford to pay more to offset future OOP risk, there is no such provision. Often, when ordinary families exhaust their savings, they sell land, take loans or resign themselves to fate.

Health insurance works by insuring many to care for a few. Currently, within the NHIP framework, there are roughly 20 percent active enrollees. Of these, many enrol because they have chronic illnesses or only when they fall sick. Consequently, the Health Insurance Board has not been able to reimburse hospitals and is struggling to stay afloat. For a health insurance model in its infancy, this can be a death sentence. This is both a design problem and a policy problem.

We need more than incremental reforms. We must reduce pressure on public funds by forming partnerships with private insurers. Both federal employees and private-sector workers should be incentivised to make payroll contributions to their health plans.

If a family can afford to increase its annual premium from NPR 3,500 to NPR 35,000, this could raise its annual coverage ceiling to NPR 1 million or more. Families should be given such choices. This would generate additional revenue for the Insurance Board. Policymakers must shift from a scarcity mindset to one of possibility and recognise that health insurance can be financially sustainable.

The Philippines has earmarked a “sin tax” on alcohol and cigarettes and uses the revenue to invest in citizens’ health. Nepal should learn from this model and impose a dedicated health tax on alcohol, cigarettes and fast food. If we can collect taxes from petroleum sales to build roads, why can we not adopt a similar model for healthcare? We can—and we should.

About 25 percent of households in Nepal have a member working abroad. We could design an innovative remittance ecosystem whereby every time a migrant worker sends money home, they have the option to allocate a portion of the transfer to their family’s health insurance plan. The government could match that contribution up to a certain amount to encourage participation.

The government should also increase its investment and raise enrolment in the NHIP from the current 20 percent to 80 percent.

These solutions are not without challenges and will require significant buy-in from citizens, the government and the private sector. But we cannot continue to lose families to curable illnesses.

When my oath to heal collides with a system built on inefficiency, doctors like me are left in a moral no-man’s land—watching patients and loved ones suffer not from a lack of knowledge or skill, but from a transactional healthcare model that can still be fixed. Nepal’s National Health Insurance Program has its problems, but if we can pull it off life support, it could set an example for the Global South to follow.

Dr Poudel is a medical oncologist currently pursuing a Master of Public Administration at the Harvard Kennedy School.